SAFE vs Token Warrant vs Tokenized Equity: A 60‑Minute Framework to Standardize Web3 Ownership

A portfolio-ready way to compare SAFE, token warrants, and tokenized equity without bespoke legal complexity. Use a five-question lens to model settlement, triggers, dilution, liquidity, and Series A diligence readability across deals.

Token warrant vs SAFE vs tokenized equity: a 60‑minute framework for portfolio-standard ownership

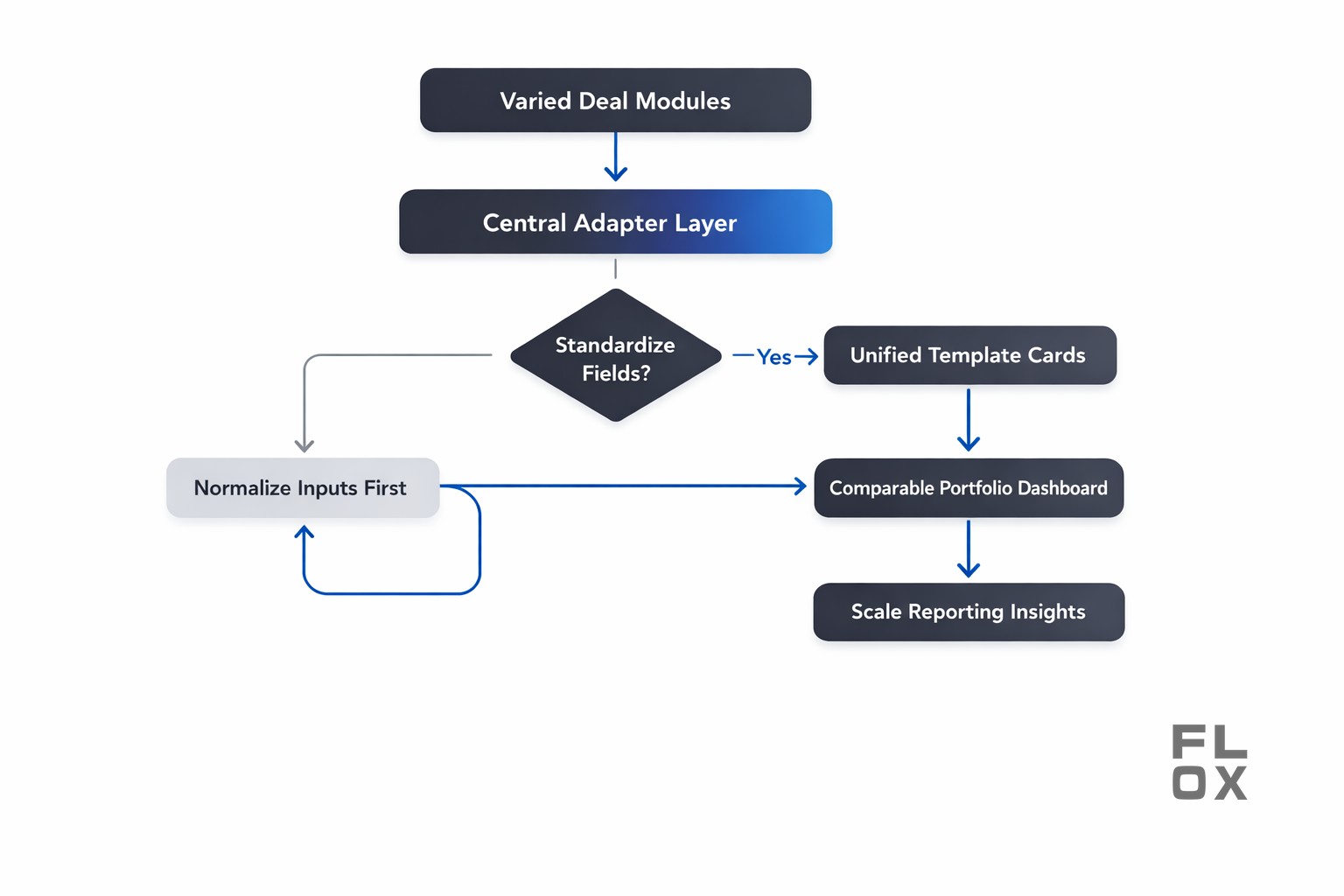

If your studio or fund is backing multiple early-stage companies, you can’t afford to reinvent ownership structure every time a deal includes both equity and tokens. The fastest way to create cap-table chaos is to mix a SAFE, a token warrant, and contributor incentives without a shared model of who gets what, when, and with what rights.

Tokenization is becoming unavoidable—whether through tokenized equity, contributor points that convert, or protocols that need onchain governance. The problem is comparability: most teams can explain each instrument in isolation, but struggle to forecast outcomes at the moments that matter (next round, governance, liquidity). This framework is designed to help you compare SAFE vs token warrant vs tokenized equity across a portfolio in under 60 minutes—without turning every decision into a bespoke legal project.

Why “comparable” beats “clever” at portfolio scale

Early-stage ownership debates usually break down because different instruments speak different languages. Equity instruments optimize for price and investor protections; token instruments optimize for distribution, governance, and network effects. Without a consistent translation layer, partners end up relying on vibe, precedent, or the loudest advisor.

Portfolio inconsistency is the hidden tax. If one company uses a SAFE plus a token side letter, another uses a token warrant with ambiguous settlement mechanics, and a third experiments with tokenized equities, you can’t explain risk cleanly to LPs or predict dilution and control at Series A.

The goal isn’t to “pick equity” or “pick tokens.” The goal is to standardize decision-making so structures remain fundable, governable, and legible when a traditional lead investor shows up.

The three primitives: SAFE, token warrant, tokenized equity

A SAFE is straightforward: it’s a contract for future equity, usually converting at the next priced round. It’s familiar to counsel, easy to model, and generally maps cleanly into cap tables and LP reporting.

A token warrant is different: it’s a contract for future tokens (or token-linked rights), typically triggered by a token generation event (TGE) or token issuance. It can be clean when defined tightly—but it often hides complexity in definitions: what counts as “tokens,” how supply is measured, and whether the holder receives governance rights, transfer rights, or economic rights.

Tokenized equity (and broader equity tokenization) attempts to represent equity interests as onchain instruments—often discussed under the umbrella of digital securities. This can improve transferability and programmability, but it raises heavier operational, regulatory, and downstream investor coordination requirements. It’s also frequently misunderstood: “what are tokenized equities” is not just “stocks on a blockchain”—it’s equity with securities rules plus new infrastructure and disclosure expectations.

Quick orientation (not legal advice)

Here are the most common “what you actually own” outcomes:

- SAFE: future equity (cap-table entry later)

- Token warrant: future tokens (network asset; may or may not have economic rights)

- Tokenized equity: equity represented in token form (security + onchain rails)

A good portfolio standard doesn’t need every company to use the same instrument. It needs every deal to be evaluated through the same lens.

The 60-minute comparison framework (five questions)

You can run this in one meeting if you force the same five questions across every opportunity. The output is a one-page “ownership brief” you can share with founders and counsel.

1) What is the settlement asset and what does it control?

Start by naming the thing delivered at settlement and the rights attached. This single step prevents most downstream confusion because it distinguishes economic upside from governance power.

Ask:

- Is the deliverable equity, tokens, or equity tokens (tokenized equity)?

- Does it include cash-flow rights, governance votes, information rights, or only transferable units?

- If tokens: are they utility, governance, fee share, or a bundle?

Then write a plain-English sentence: “Holder receives X% of Y, with Z rights, subject to A restrictions.” If you can’t write that sentence, you don’t have a structure yet.

2) What are the trigger events—and can you model them?

Most failures happen because trigger events are fuzzy. A SAFE typically triggers on a priced round; token warrants trigger on token creation/issuance; tokenized business equity may involve issuance, transfer restrictions, and compliance gates.

Standardize triggers into a small set:

- Financing trigger (priced round, change of control)

- Token trigger (TGE, first mint, mainnet launch)

- Time trigger (long-stop date, expiration)

- Compliance trigger (KYC/AML, jurisdiction gating)

If a trigger depends on “when we feel ready,” it is not modelable. Portfolio standards require modelable events.

3) How does dilution and supply expansion work?

Equity investors think in dilution; token holders think in supply and unlocks. You need both views on one page.

For each structure, define the dilution mechanics:

- SAFE: pre/post-money, valuation cap, discount, pro rata treatment

- Token warrant: % of initial supply vs fully diluted supply, inclusion of reserves, staking rewards, future emissions

- Tokenized equity: equity dilution rules still apply; token supply is not the question—share count and transferability are

If the token warrant references “total token supply” without defining whether it’s initial, fully diluted, or including future emissions, you have an ambiguity that will become a dispute.

4) What is the liquidity path—and who controls it?

Liquidity is not a single moment. Equity tends to liquidate via M&A or IPO; tokens may have earlier market liquidity but more governance and regulatory sensitivity. Tokenized equities may offer improved transfer rails, but the liquidity path is constrained by securities compliance and market structure.

Force every structure into one of three liquidity narratives:

- Equity-led liquidity: exit event determines payout; tokens (if any) are secondary

- Token-led liquidity: token market provides earlier liquidity; equity may lag

- Hybrid liquidity: some rights liquid earlier (tokens), some later (equity)

Write down who controls timing: the company board, the protocol governance, or market conditions. If you can’t identify the control point, you can’t manage expectations.

5) What does Series A diligence “see” on paper?

This is the portfolio-protecting question. A Series A lead will ask: what are the rights, obligations, and off-cap-table promises? If your answer requires a long oral explanation, you will lose time or the deal.

Run a “diligence readability” check:

- Are rights and settlement terms contained in standard documents?

- Are side letters minimal and consistent across investors?

- Are contributor incentives documented with vesting, scope, and dispute process?

- Can counsel map the token warrant (or tokenized equity mechanics) to a clear cap-table narrative?

Your goal is not to avoid innovation. It’s to ensure the structure remains legible under pressure.

A practical scoring sheet to standardize decisions

After answering the five questions, score each structure so partners can compare deals quickly across geographies and counsel preferences. Keep the scoring simple and consistent.

Use a 1–5 score (low to high) for:

- Model clarity (can we simulate outcomes at triggers?)

- Governance clarity (who votes on what, and when?)

- Diligence readiness (will a traditional lead accept it?)

- Regulatory surface area (how much uncertainty are we carrying?)

- Operational load (reporting, custody, compliance, administration)

Then add one sentence: “We accept this structure because X, and we mitigate Y by Z.” That sentence becomes your internal precedent.

Common failure modes (and how to preempt them)

A token warrant often fails not because it exists, but because it’s underspecified. The same is true for contributor points that quietly promise future tokens without a clear plan.

Watch for these recurring issues:

- Undefined token supply basis (initial vs fully diluted vs emissions)

- No long-stop date (warrants that never settle but never expire)

- Governance mismatch (tokens confer control without accountability)

- Contributor promises off the record (no vesting or dispute process)

- Liquidity story incoherent (who can sell, when, and under what restrictions)

Preemption is mostly documentation discipline: clear definitions, explicit triggers, and a scenario model that matches the documents.

Conclusion: make the token warrant comparable, not controversial

Studios and emerging funds don’t need a single “right” answer to equity vs tokens. They need a repeatable way to compare a SAFE, a token warrant, and tokenized equity so every deal can be explained, modeled, and diligenced without cap-table surprises.

If you want a scenario-first way to standardize these decisions across a portfolio—so you can pressure-test governance, dilution, and liquidity before you sign—use Flox Capital’s frameworks to make web3 ownership decisions with clarity: Make web3 ownership decisions with clarity.